What are civic apps for?

One of the wonderful things about civic technology is that no one really knows what it means. ‘Civic technology’ covers varying types of projects made by a variety of people trying to do very different things. This fuzziness is useful. It challenges civic technologists to think independently about what exactly they are trying to do, while providing a wide set of projects and models to steal from or define themselves against. All the same, we can begin to identify four major intentions of civic apps.

Published September 11, 2014

One of the wonderful things about civic technology is that no one really knows what it means. “Civic technology” covers varying types of projects made by a variety of people trying to do very different things. This fuzziness is useful. It challenges civic technologists to think independently about what exactly they are trying to do, while providing a wide set of projects and models to steal from or define themselves against.

All the same, we can begin to identify four major intentions of civic apps: to inform, to persuade, to provide access, or to change the way our democracy works. These correspond to four genres of apps: news, propaganda, access, and system plumbing.

Civic apps either promote communication or action. Additionally, civic apps are either “ends” or “means” apps. For “ends” apps, people using the app is the point. In “means” apps, people using the app is good if it helps achieve some other end.

These two differences cross cut, and we get our four genres.

| Ends | Means | |

| Communication | Informing the public | Propaganda |

| Action | Access | System plumbing |

Communication apps structure a complicated issue or proposal so that the public can understand it. The point of these apps is either an end—informing the public, or a means—to win a public debate by persuading the public.

Action apps make it easier for people to do something. The point is either an end—access to the action, or a means—the action helps something else happen.

For example the difference between an “ends” and “means” action app is the difference between promoting voting because you think everyone should vote, and attempting make it easier to vote because it will help elect a particular politician.

All of these genres can and do blend in real apps, but it’s helpful to discuss them discretely.

Let’s dive in to each type of app:

Informing the public

Communication & Ends

These civic apps are attempts to explain or show something about government or a social problem. Informing is the whole point, not means to some other end. These are a basically news apps, and the developers are often working as a kind of citizen-journalists.

The technology of the citizen news app tends to be about beautiful, visual simplifications of complicated information, interactivity, and personalization. They provide a fun, relatable, and engaging means of learning about an issue. When done well, they tend to spread easily on social media.

On the back end, news apps often depend upon open data, and powerful, free tools for data processing and analysis.

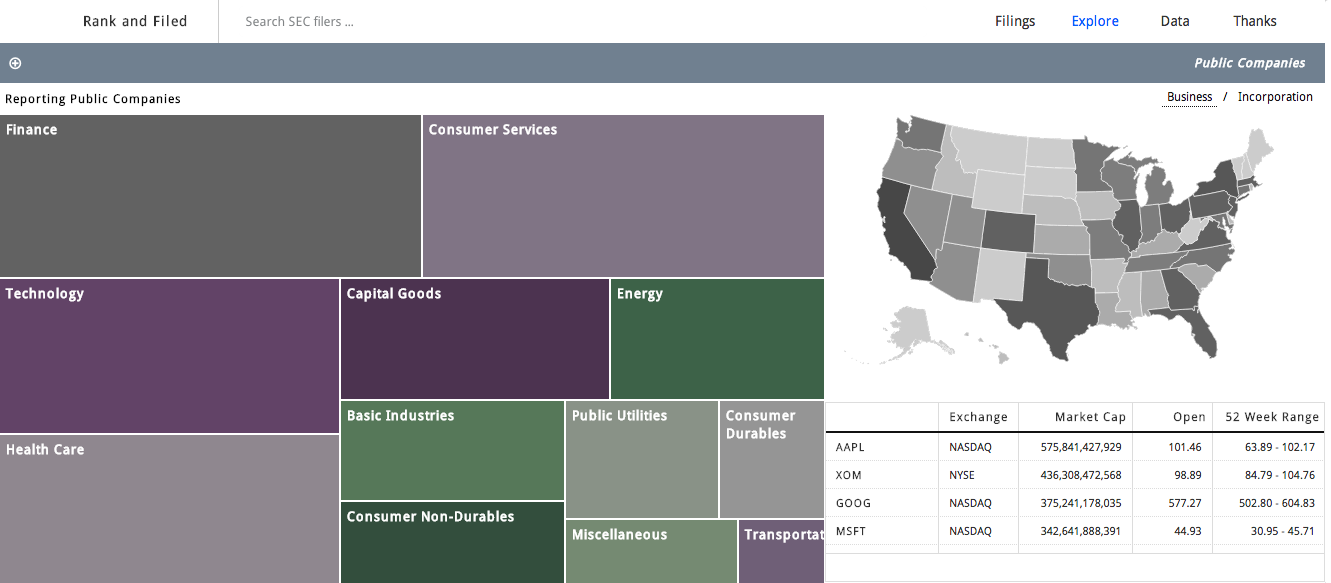

Rank and Filed explores SEC filings

Other examples of news apps:

- ChicagoCrime.org - view historical crime reports on a map (the precursor to EveryBlock)

- Rank and Filed - SEC filings for humans

- Political Party Time - When and where are the political fundraisers?

- Second City Zoning - look up the zoning for any address in Chicago

- NYC Taxis: A Day in the Life - displays the data for one random NYC yellow taxi on a single day in 2013

- ClearStreets - track where Chicago snow plows have gone during a snowstorm

We can evaluate the effect of citizen news apps by asking:

- How many people are being informed by the app?

- What kind of people are able to access this resource?

- Does the app explain something worth knowing?

- Is the app accurate?

Propaganda apps

Communication & Means

Many of the decisions about the nature of our city, state, and country are never debated in public, because they are successfully sold as an unpolitical, technical solution to a clear and important problem. The classic examples are big highway plans, school reorganizations, and urban renewal projects.

Opponents to these kinds of policies haven’t had many good moves. In a direct attack, critics are usually hobbled by poor access to information and little expert staff or resources. Even when opponents have the technical capacity, it can be hard to explain to the public why their complicated analysis is better than the original complicated analysis. Why should we trust this group of experts more than the other?

These conditions are changing.

First, because of open data and free, powerful data tools, it is now much cheaper for researchers to evaluate the technical justifications of alternative proposals.

Second, With the same techniques used in creating news apps, advocates can also explain complicated policy arguments in relatable, personal, and, most importantly, shareable ways. Instead of asking the public to trust her expertise, the advocate structures her argument so that the public can follow and evaluate it. These are “propaganda apps”: technologies of persuasion.

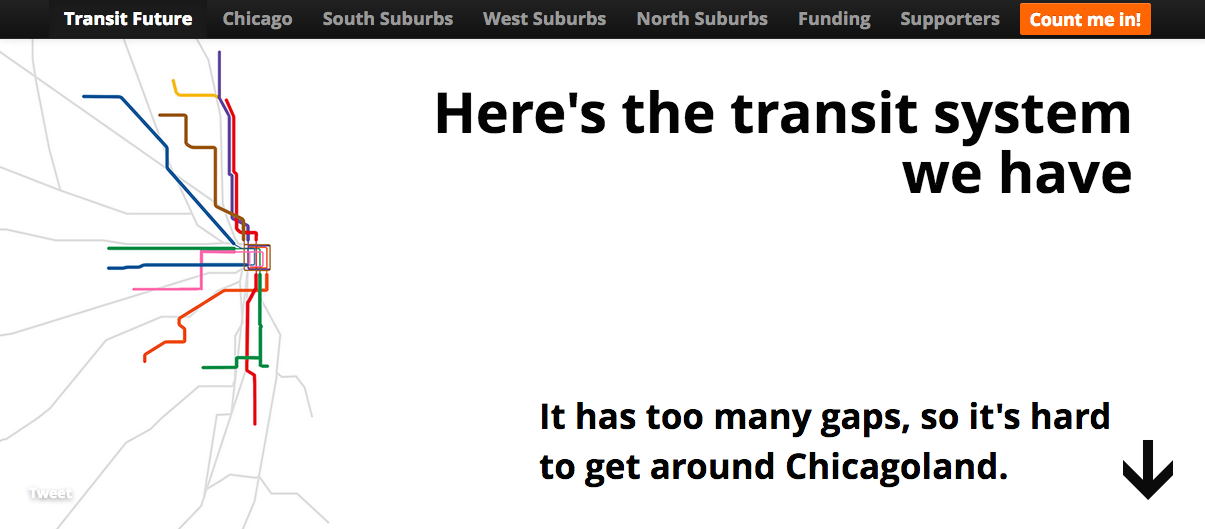

In Chicago, the best example of the “propaganda app” is TransitFuture.

TransitFuture promotes an expansive plan to increase public transit in Chicago

In Summer of 2014, two Chicago transit policy research organizations, the Center for Neighborhood Technology and Active Transit Alliance, published an incredibly ambitious and complicated plan to increase public rail and bus lines in the Chicago area. In addition to the typical press releases and fact sheets, a very small team put together a website that explained, bit by bit, what the plan was, who it would affect, and why it was necessary.

The website was beautiful, interactive, and completely understandable. The site was shared more than 14,000 times on Facebook and had over 125,000 unique viewers in the first month.

Other examples of propaganda apps:

- Justice Atlas and Million Dollar Blocks - mapping prison sentencing and admission rates

- Inequality.is - interactive app for pursuading the user about the issue of income inequality in the US

- U.S. Gun Deaths - an examination of the gun killings in the United States

- SchoolCuts - an app targeted at parents for understanding the closing of 54 Chicago Public Schools in 2013

We can evaluate propaganda apps by asking:

- How many people are being exposed to the app?

- What kind of people see it?

- Does the app convince the audience?

- Is the app accurate?

- What kind of follow-through does the app generate?

Access apps

Action & Ends

Access apps remove unfair barriers to an action. The primary goal for these apps is not to get a lot of people to do something, but rather to open up a process to people who have been excluded. These apps reduce the amount of time, English literacy, bureaucratic literacy and even interest required to do something.

Google Civic Information API allows you to look up elected officials and election info

Most access apps are attempts to make it easier to navigate some government service or process:

- Google Civic Information API - look up elected officials, polling places, early vote locations and candidate candidates for the US

- RecordTrac - making it easier for Oaklanders to make public records requests

- Long Distance Voter - get your absentee ballot

- Expunge.io - help people expunge their juvenile arrest records

- Large Lots - online application for purchasing vacant, city-owned lots in Chicago

We can evaluate access apps by asking:

- How many people are being exposed to the app?

- What kind of people see it?

- How many people completed the action because of the app?

- What types of people are using this app?

- How much time did people save because of the app?

- Would it have been better to work with government to fix their process?

- Would it have been better to work to change the policy that created the process?

System plumbing apps

Action & Means

Our democracy is complicated. It’s not so clear why one person wins an election and another doesn’t, why some parts of a city are rich and healthy and others are poor and sick, why some things are on the news and others aren’t. We come up with theories to explain what we see, and right now, most of our theories are about how the volume of messages and money determine politics.

For example, you might think that Congress has not passed legislation to address climate change because oil companies have more influence over congress than environmentally concerned citizens. Or, you might think that recent set of defeats of traditional marriage between a man and woman is because of the liberal media’s influence on public opinion.

The problem, it seems, is the volume of the flow of messages and money. To make our society better, we have to change the flows. System plumbing apps attempt to change the flows by making it much easier for people receive messages, send messages, or give money. While access is often improved, the real point is to increase volume.

HearFromYourMP enables new channels of communication between elected officials and their constituents in the UK

The cleanest example is MySociety’s HearFromYourMP. On this service, UK residents sign up to get an email of updates from their representatives (“Members of Parliament” or MPs). When 25 people have signed up for a district, the MP gets an email that says “25 of your constituents would like to hear what you’re up to. Hit reply to let them know.” If they don’t reply then nothing happens until 50 people sign up, and then the MP is notified again, and again at 75, 100, 150, etc.

These action apps correspond to the techniques of Tom Steinberg’s Regime Changing and Citizen Empowerment Organizations. He does a great job describing these efforts.

Plumbing apps include:

- EveryBlock and NextDoor - share neighborhood information

- AskThem - publicly ask questions of your elected representatives

- Fix My Street and SeeClickFix - publicly report on neighborhood issues

- Change.org - online petition platform

- VoterVault and Demzilla - registered voter databases

- InfluenceExplorer - tool to see who gave campaign contributions to whom in order to dampen the most naked forms of political corruption

We can evaluate system plumbing apps by asking:

- Do the developers have a good theory of how their corner of the world works? If the app is very successful in generating action, will that actually change what they want to change?

- Can the app do any good before it reaches a large scale? If no, do the developers have a credible plan to reach that scale?

- If the world changes the way the developer wants, who will be the likely winners and the likely losers of power?

What’s missing?

These genres don’t cover every app that has ever been called civic technology. We know. Some apps, particularly the startups coming out of Code for America’s Accelerator are more about improving the operations of governments, like OpenCounter and SmartProcure. Some apps are solving private problems and happen to use public data, like Google Transit Directions. These are all great apps, they just are a different kind of thing in our view.

For more on this topic, take a look at the writings of Tom Steinberg , Micah Sifry and Ben Sheldon’s Civic Tech Patterns or see the notes from our session on Building Civic Apps that Have an Impact at Transparency Camp.