Machine Assisted Dossiers

Existing research tools make it difficult for teams to pursue investigations when source material is uncertain or contradictory. This whitepaper outlines the requirements for a knowledge system that can manage ambiguity during investigations and produce useful, structured data as a byproduct.

Published November 14, 2017

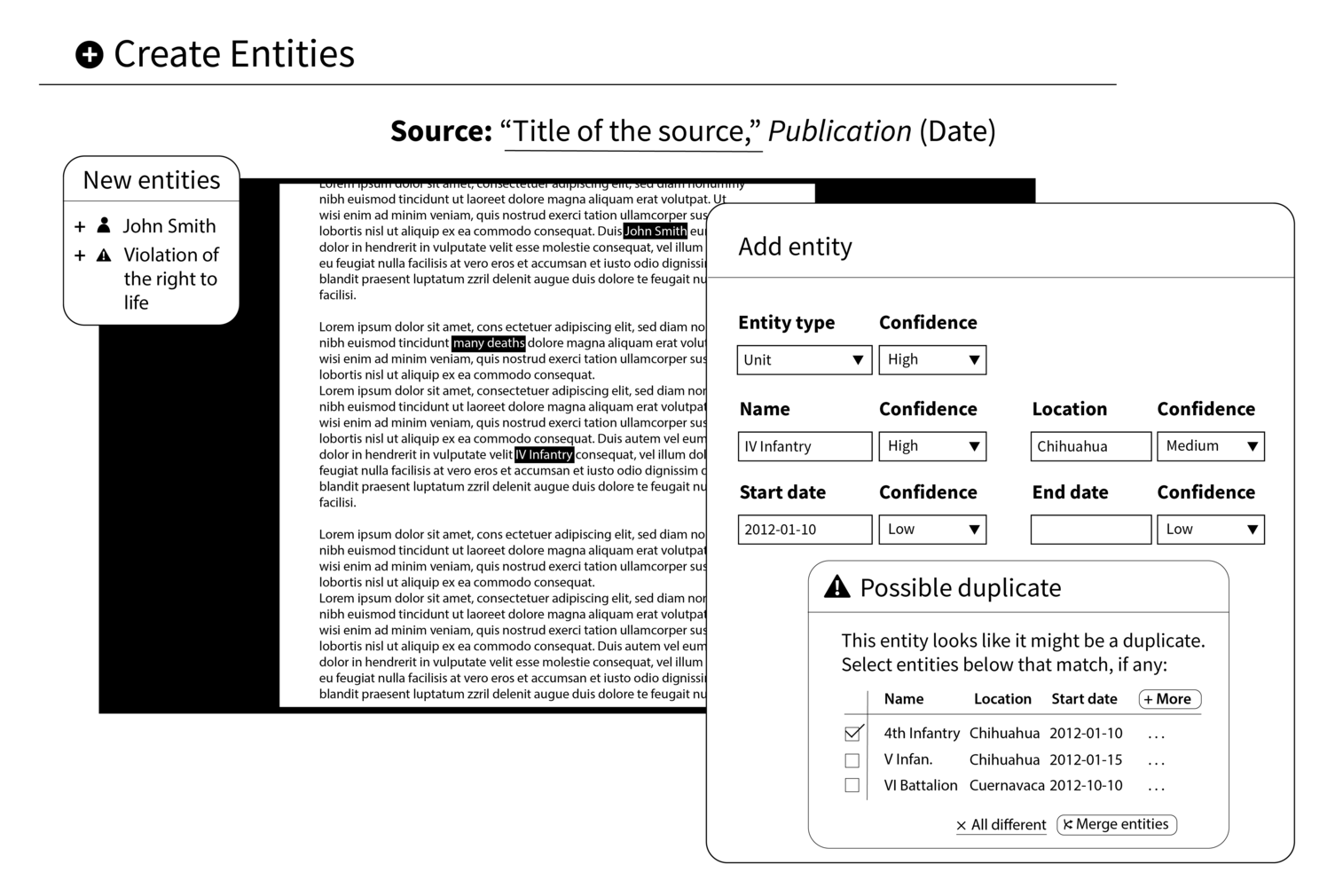

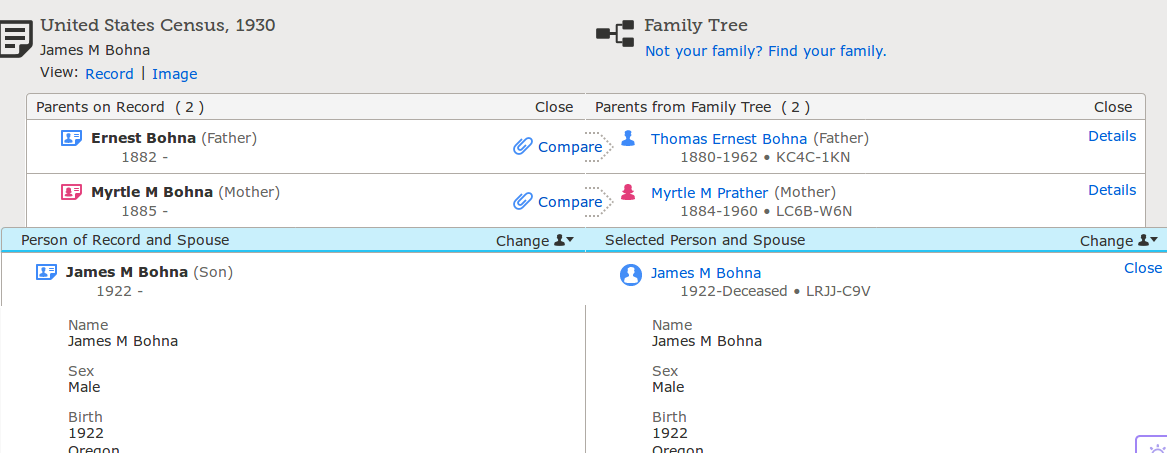

An imagined interface for creating entities in a machine assisted dossier.

This is a version of a paper that we presented at the Computation + Journalism 2017 Symposium. Read on, or download the PDF.

Abstract

One of the great disappointments of data journalism is that so much available data is simply bad. It is unreliable, ambiguous, and contradictory. Developing an accurate image of the world still requires discernment, sorting, and judgment.

We are still only beginning to build technologies that complement these human capacities—but allow them to scale. In this paper, we present the capabilities we believe an adequate knowledge system must have, drawing heavily from the field of genealogy and our own work modeling international security forces.

We’ll discuss the overall requirements for such a system and try to envision its user experience and its data architecture; we’ll also survey where currently available technologies can fill in the gaps between the two.

Introduction

Most of the time, investigative journalists use data and documents that were not made for them. The material that they FOIA, scrape, get leaked, download from data portals, or dig up from the archives were not made for journalists or intended to help answer the questions they are reporting.

In order to do their work, journalists have to struggle to get access to documents or administrative data; manage large collections of source files; extract the relevant information; identify ambiguous references; and reconcile conflicting claims.

That journalists accomplish these tasks, and that they do so relatively quickly, is a testament to their skills as researchers. These skills, however, are private, and focused on the investigations at hand. The work does not accumulate a store of knowledge that can be reused by future journalists for new investigations.

The promise of computers, meantime, is to offer speed (enabling the analysis of larger corpora of source material), scale (enabling the analysis of larger webs of interrelated facts), and memory (enabling knowledge to be stored and shared, whether for reproducing an analysis or for bringing the knowledge to bear on a new problem).

Though journalists and newsrooms would benefit from building shared dossiers of the key people and organizations in a beat, this is not a common practice. The reasons for this are various, but we believe a substantial barrier is that existing tools do not provide immediate benefits to a journalist in the middle of an investigation. It may be very helpful for a journalist to look up what the newsroom already knows about a city councilor in an internal wiki, but adding new content to the wiki is just an additional chore.

At DataMade, we have been building and researching knowledge management systems that can help investigators in the many stages of research and which, almost as a byproduct, produce shared dossiers of people and organizations. In this paper, we discuss the capabilities that a well-designed system should possess, from the perspective of information architecture and end-user experience.

Existing Tools

Existing knowledge management systems prioritize flexibility for the individual researcher over general utility for a team, or for a wider audience.

When individual researchers are afforded flexibility to organize information as they please, the information is almost always put into a form that suits the researcher’s personal preferences and their current research topic. Considerable work is required to recontextualize the information into a form that is convenient for other uses. Conversely, when data must be organized to support the general uses and users, researchers usually lose capacity for tolerating ambiguity, and the tool is not perfectly adapted to the current project.

Here, we consider the affordances and limitations of a few of the most popular tools for knowledge management in research contexts.

-

Notecards. Collecting and organizing analog files remains a popular research method, for good reason. Using notecards, an individual researcher is free to organize and reorganize a knowledge system however she pleases. Notecards neatly illustrate the tradeoff between flexibility and utility involved in designing a knowledge system: they offer total control to the individual researcher at great cost to the general public, for whom the system must be painstakingly translated to be of any use at all.

-

Scrivener. Composition tools like Scrivener port the visual and mechanical metaphors of analog research methods to digital contexts. With these tools, information can be recorded in digitized form, but it is still completely unstructured. The individual researcher is able to keep track of more and more different kinds of information, but translation is still required in order for others to make sense of it.

-

Wikis. In contrast to notecards and digital composition tools, Wikis prioritize the needs of a collective of stakeholders over the individual researcher. Information is sometimes structured and attached to specific sources, and the process that produced the knowledge can be preserved in discussion forums. In a wiki, however, individual researchers lose a great deal of power in order to create value for the collective: knowledge is subject to collective approval, and conflicting truth claims must be reconciled fully and immediately.

Scope Conditions

In order to provide more support for journalists and other researchers, a system must be designed for a defined universe of knowledge to manage—the types of organizations, persons, and events; the attributes of those entities; and the relations amongst them.

With these set, the designer of the system can identify source material with potential relevance, what pieces of information will be important in the source material, what facets of the information will be useful to index, and what types of claims are congruent or incompatible.

The more defined the field of knowledge, the more that information technology can aid the production of that knowledge. However, given the current costs of building, a limited field of knowledge is not sufficient. These types of systems should only be built where three conditions are met. First, there is a fairly narrow knowledge area that has wide and durable interest. Second, the number of concrete instances of knowledge is much larger than one person can manage using private skills. Third, there is a large corpus of primary source material that can be used to develop concrete knowledge in a repeatable and separable manner.

Some examples include:

-

Geneology. Who were the parents of whom. When and where was a person born and when and where did they die.

-

Corporate Beneficiaries. Who ultimately owns or controls an organization, which may be owned by a chain of shell organizations.

-

Security Forces. What is the organizational structure of security forces. Who are the commanding officers of units and what has been their careers.

-

Campaign Finance. Who, ultimately, gave money to which political campaigns, directly or through intermediaries.

-

Human Rights Violations. Who and how many people have been killed in an armed conflict.

-

Customer Relationship Management. The nature and relationships of individuals and organizations; the history of contacts between them.

Consider two different organizations, both working in one of these problem domains, both with separate missions but similar sets of problems:

Security Force Monitor is a nonprofit based out of Columbia University with the mission of tracking security force activity in conflict areas around the world. Maintaining a robust knowledge system is a key part of their mission, but it is a difficult task: keeping track of security forces requires keeping track of large quantities of ambiguous information—information that has been retrieved from unreliable sources, primarily secondary news reports, and that is then adjudicated by staff members who lack authoritative context. For any given assertion about a human rights violation to be credible, the knowledge system must know where each piece of information came from, which researcher catalogued it, and the degree of confidence the researcher had in the assertion. Yet for the system to be useful to an audience outside of the internal research team, it must also be capable of adjudicating conflicting claims and presenting a structured view of the security forces and the incidents they have been involved in.

FamilySearch is a service provided by the Church of Latter-day Saints that seeks to build detailed genealogies using demographic records. The service sources much of its information from old census records, which are OCRed and then interpreted by staff members, but it also allows users to upload their own records and contest genealogies recorded by the system. Every claim must be tied to a specific record, and contested assertions are eventually adjudicated.

As we describe the necessary features of machine-assisted dossiers, we will refer back to the problems and solutions that these two organizations engage with in their attempts to build comprehensive knowledge systems.

Document Management

The system must have the capability to collect the source material which will be the evidence to support the development of knowledge and make those materials convenient for the purposes of research. The set of problems here are largely covered under the field of document management and there already exist many excellent tools for this portion of the task. Within journalism, the prominent examples include DocumentCloud, aleph, and the PANDA project.

For our purposes, we are using “document” to mean any type of source material. Documents are most often different types of files: word processing files, PDFs, markup, spreadsheets, etc. They could include audio testimony, news articles, or FOIAed records.

Beyond storage, the three key capabilities for the document management portion of the system are: capturing the provenance of source material; converting the source material into convenient formats; and indexing the documents in support of research.

Provenance

As the knowledge developed within the system ultimately depends upon source documents, the provenance of those documents must be recorded: who or what (if it was an automated scraper) collected the material, when, and from what original location. The original forms of the documents must be preserved.

Formatting

Often, source material is not in a convenient format for computer processing. A file may be in an awkward or proprietary format, or a document may only be collected as scanned image. As part of the research process, the material may be converted to a form that allows for easier processing. Sometimes this conversion is unproblematic, like for many file format conversions. Sometimes, the conversion is very error-prone, such as OCRing a scanned document or human transcription of audio recordings.

Regardless, the details about the conversion need to be recorded—who or what did the conversion and when. If the process was done by a computer, steps must be taken to ensure that the conversion is completely reproducible. As technologies or other capabilities improve, the journalist or researcher may want to reconvert existing documents, and conversion metadata can support this goal.

Indexing

Finally, appropriately formatted documents should be indexed for the next stage of research. While the systems should do full-text indexing to allow for flexible searches, the system should also attempt to index the documents on facets relevant to the target knowledge area. This means that the system should attempt to identify references within a document to the types of people, organizations, places, and events that the overall system is concerned with.

If the source material is already highly structured, this can be simple. However, if the material is free text, then the system should attempt to identify references using Named Entity Recognition techniques.

Indexing is the most basic form of computer analysis of documents. It enables non-trivial analysis of topics and relevant entities through simple counting and co-location analysis, and when combined with minimal provenance data (chronology), can provide evidence of change over time. Indexing also provides the basis for building a database of named entities.

Entity Management

Once we have secured our documents, regularized them, and indexed them, producing a searchable list of entities is rewarding both immediately and in the long term. “What do we know about Jane Tye?” is a question that can be usefully answered with a keyword-in-context (KWIC) search, even when the search produces hundreds of hits. Entity management also can entail using machine learning techniques to preliminarily classify entities. This may entail sifting out individuals from organizations, or well-connected individuals from peripheral ones, but we can start to see the basis for machine-assisted analysis of large data sets.

Claim Management

Once the documentary base is prepared, the work of extracting claims about the world from those documents, resolving those claims to reference particular entities, and reconciling conflicting claims can begin. Unlike document management, the practices for what we call “claim management” are still developing.

Extracting Claims

Given a source document, a journalist will extract claims relevant to the entity of interest. If she is researching campaign finance, she might be interested in extracting the claim that “John Smith” gave $500 to “Citizens for Better Citizens” on December 11, 2017 from a financial disclosure form of the “Citizens for Better Citizens” political action committee.

While the system should allow the journalist to extract the claims in the most natural, practicable manner, the system should also decompose compound claims into simpler claims. For example, the above claim could be broken down as follows:

- “John Smith” made a contribution to this committee

- “John Smith” made a contribution during the reporting period of this disclosure

- “John Smith” made a contribution to this committee on December 11, 2017

- “John Smith” gave this committee $500

- somebody gave this committee $500 during this reporting period

- somebody gave this committee $500 on December 11, 2017

Extracting claims is effortful. While full compound claims are often incorrect in some particular, elements of the claim can often be maintained and this decomposition preserves some of the initial work.

The types of claims that can be recorded are those that the system has been designed to handle. The system must capture and preserve data on who or what extracted the claim and when this extraction occurred.

Resolving Claims

In the cases we deal with, there is almost always ambiguity about which particular entity a claim in a document is about. While a journalist will believe she is extracting a claim about a particular person or organization, she can find that she has been mistaken. Using the above example, a journalist can mistakenly attribute a campaign contribution to the wrong “John Smith.”

The knowledge system must allow for this type of ambiguity by avoiding modeling extracted claims as claims about particular instances. Internally, an extracted claim attached to a particular dossier would be modeled as two related claims. The first is the one extracted from the document: “A person with the name ‘John Smith’ gave $500 to this committee.” The second claim is “The person who is referenced in the extracted claim is the person who this system uniquely indexes with the unique identifier ‘1313515’”.

If claims about particularly people are split in this way, then extracted claims can be reassigned to the correct entities as the journalist develops a more accurate picture.

Reconciling Claims

Since the knowledge system works within limited fields of knowledge, the system designers can elaborate a model of how this portion of the world should operate. This can allow for the flagging of claims that are logically incompatible. For example, campaign committees have founding dates, so there should be no contributions from a campaign committee before it was founded.

With or without the help of system, the journalist must decide which claims are compatible and decide which, if any, she wants to accept. The system must be able to record the journalist’s belief in the validity of a claim about a particular person or organization. These decisions should be reversible.

Example Designs

Researcher use of the system will be organized around number of tasks:

-

Creating an entity. The user must be able to create a new profile page for an entity, either from scratch or through accepting a system proposed entity.

-

Viewing information about an entity. Users must be able to inspect all the information about an entity that the system knows. Users should also be able to save particular views that are relevant to their own research avenues.

-

Adding and editing information about an entity. The system must record all changes made to entity attributes and maintain a complete audit log. All modifications to an entity should be tied to a document.

-

Search entities. The user must be able to search for profiles of existing entities using full text search or faceted search.

-

Search documents. The user must be able to search source documents using full text and faceted search.

-

View details about documents. The user must be able to view any metadata about any individual document, including the raw source material itself, e.g. the scanned image. If the system has attempted to extract data from the document, this should be visible next to the source document.

-

Correct extracted document information. If the system attempts to extract data from documents, the system should allow users to correct incorrect extractions. This should be fully auditable.

-

View high order structure. The system must be capable of displaying the structure of the entities that users are tracking in order to suggest points of conflict and indicate new opportunities for elaboration.

-

Merge entities. In cases where entities turn out to be duplicates of one another, the system must provide an interface for resolving the entity into a canonical representation.

In order to assist the user, the system must be responsible for the following tasks:

-

Propose potentially relevant documents. When relevant to the user’s task, the system should propose documents that might contain relevant information about an entity.

-

Propose possible entities. When relevant to the user’s task, the system should propose the existence of an entity that seems to be referred to in one or more source systems.

-

Warn of logically conflicting information. When the user enters in information about an entity that is logically impossible, the system should warn the user.

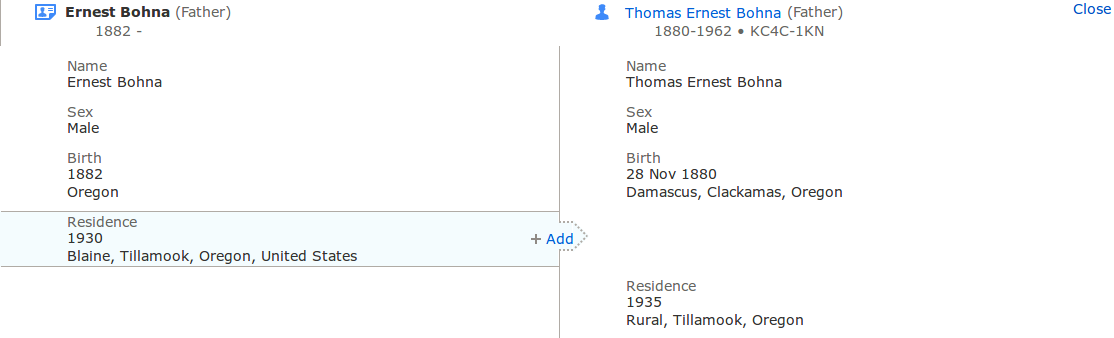

We now provide example interfaces for how these tasks can be accomplished.

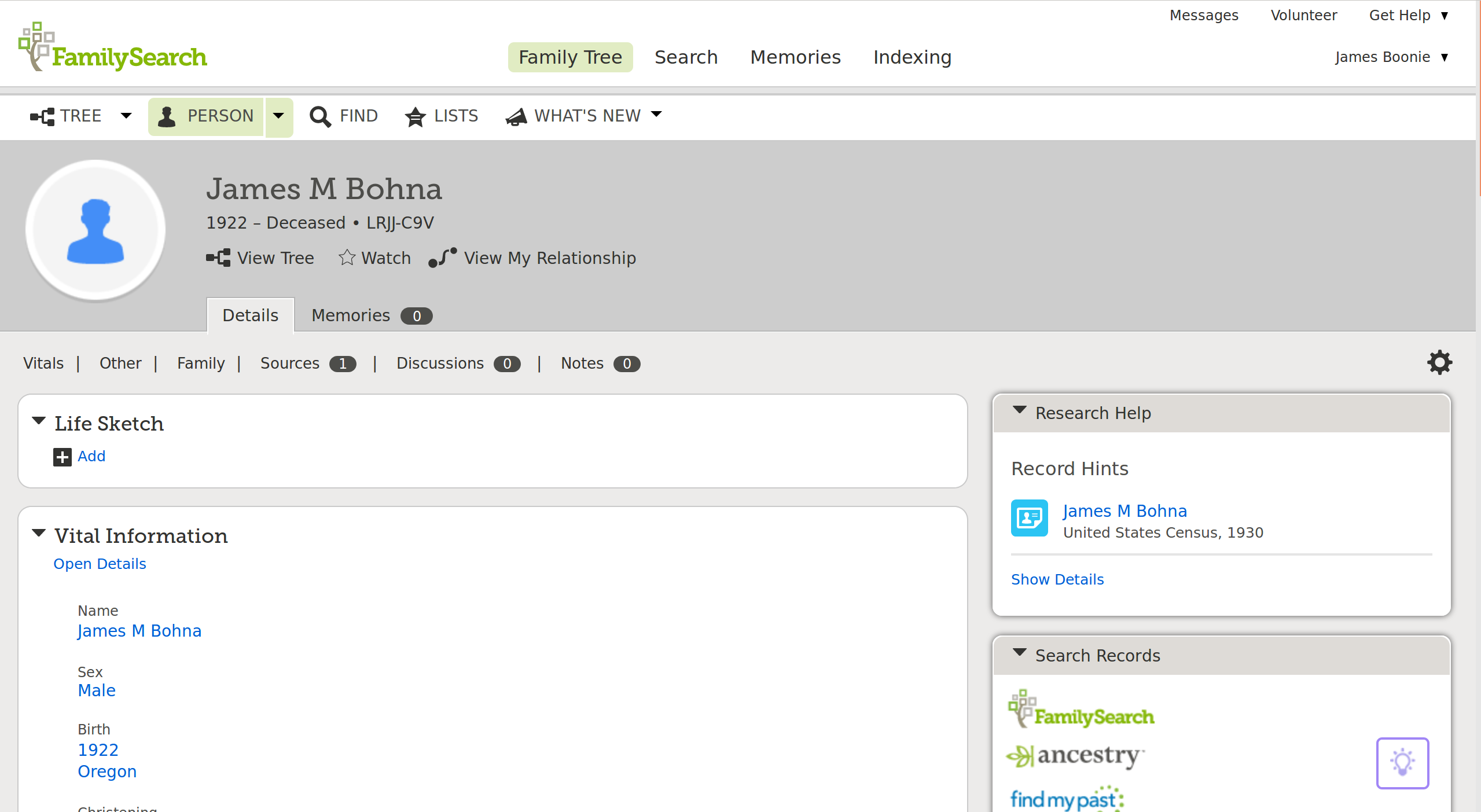

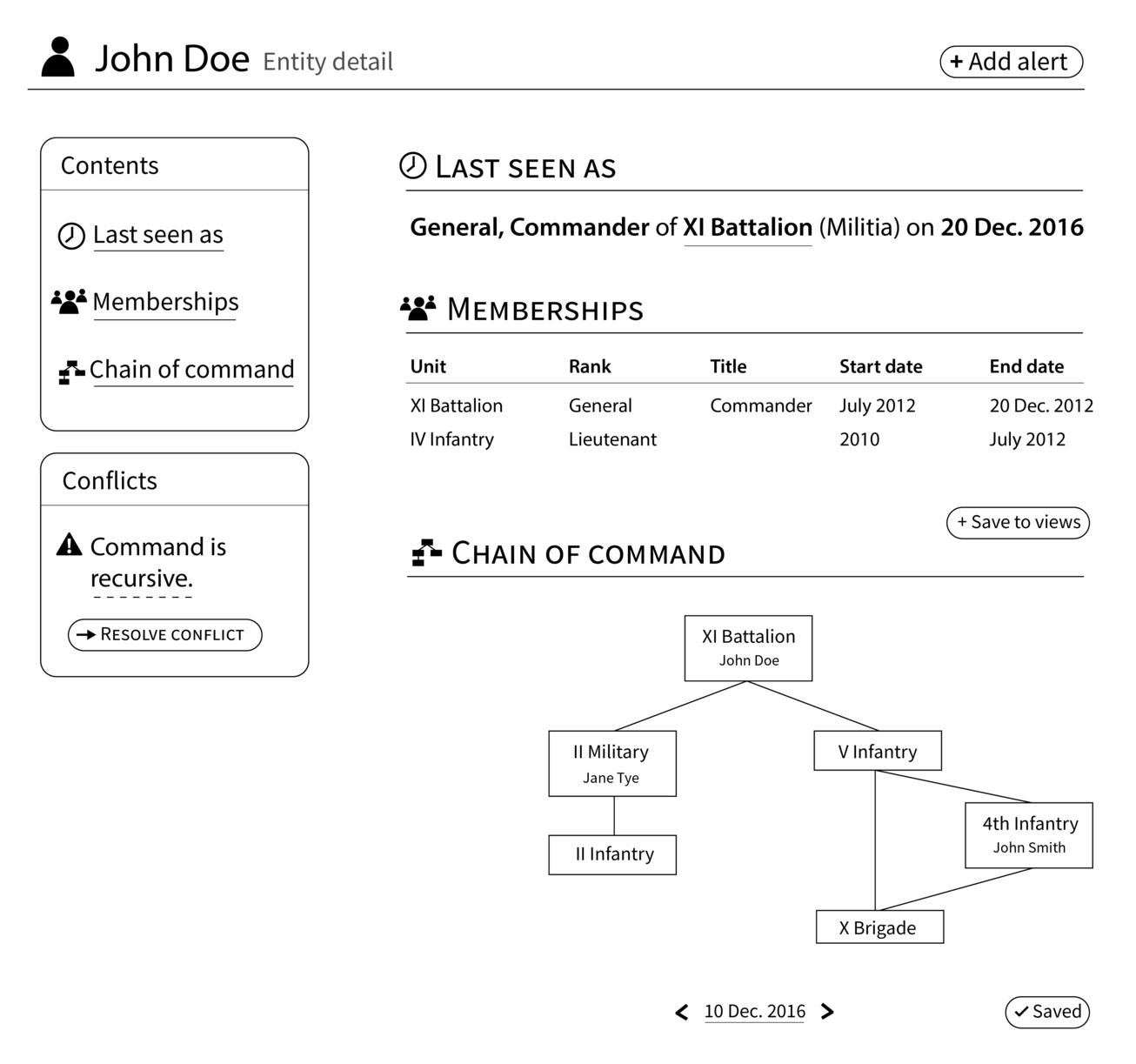

FamilySearch Implementation

These tasks are best elaborated in a discussion of concrete implementation. The most sophisticated implementation we have seen is FamilySearch.org, a geneology site operated by the Church of Latter-day Saints.

Person Profile Page

FamilySearch has a profile page for a current person in their system. The page contains an impressive amount of information and functions without overwhelming the user.

FamilySearch Person Profile Page

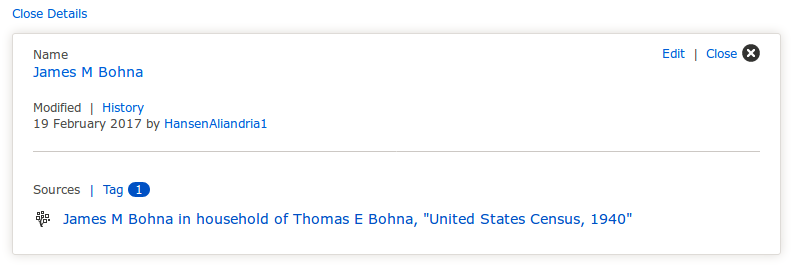

The site includes all the information that users have claimed as true about this person. Clicking on a piece of information shows the details about the claim for inspection—the user that made the claim, when the claim was made, and the source record that supports the claim.

Claim Details

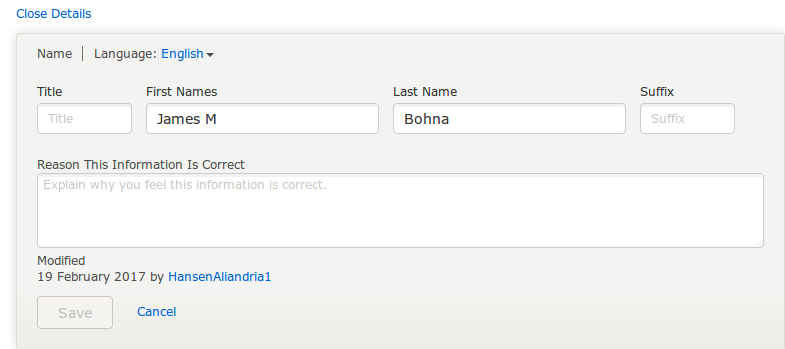

New claims can be made in this detail view. The system will record the user that made the claim, when it was made, and the justification for the claim.

Adding Claims

The profile page can also suggest source records that might be relevant to this person.

Source Record Suggestions

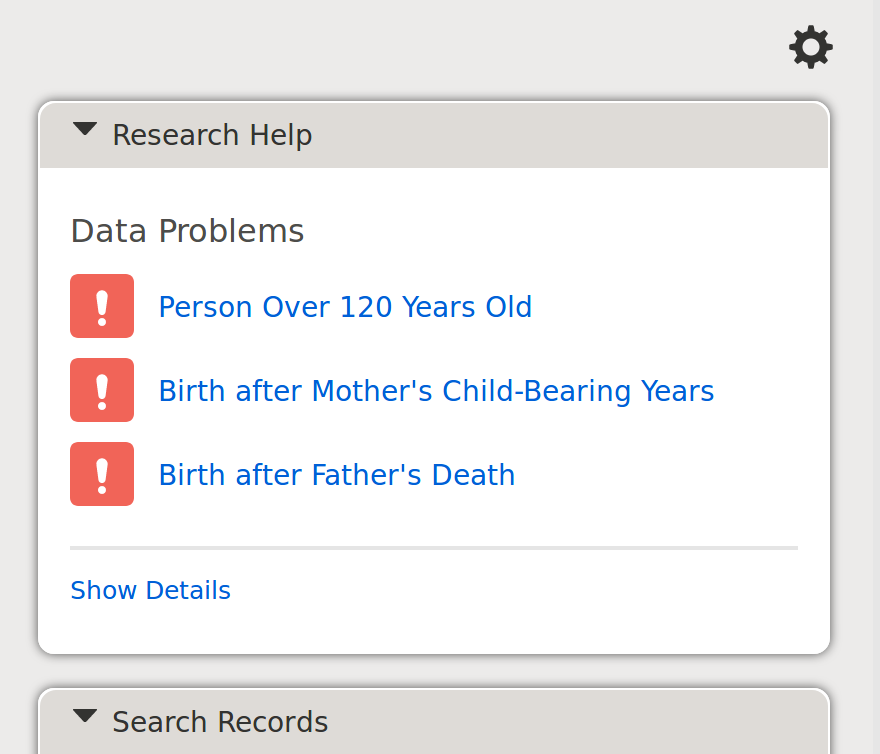

If the claims made about a person are logically impossible or just very unlikely, the profile page shows these concerns. FamilySearch allows users to enter logically impossible claims, but warns viewers of the page that not all claims about a person are congruent. Another system could decide to not allow users to enter logically impossible claims.

Unlikely or Impossible Claims

Record Search and Interface

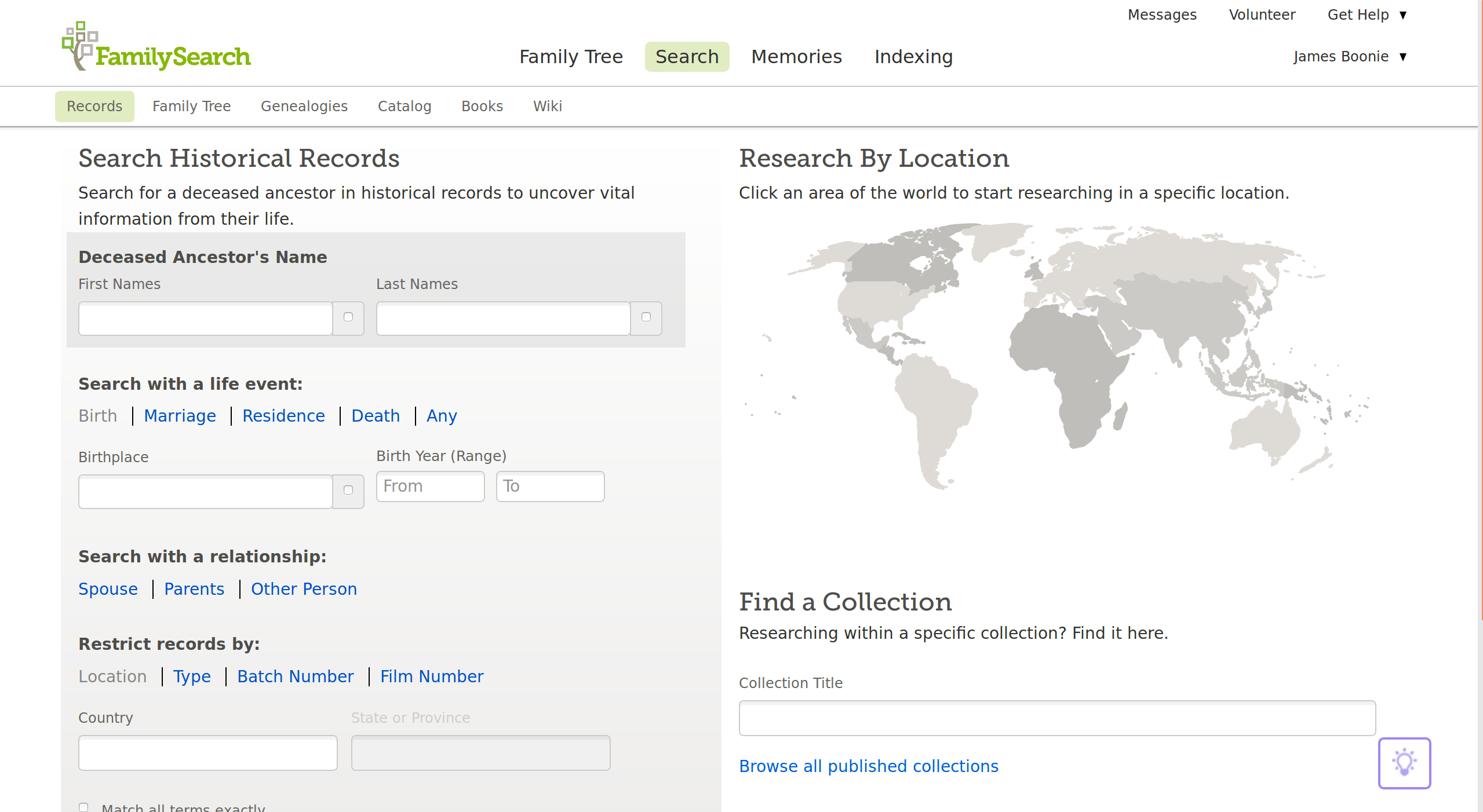

While users can directly make claims about persons on profile pages, the system strongly encourages users to make claims about people through the source record detail interface.

Working with source records starts with the search page. Users can search by name, location of important life events, or the names of important relations to the focal person.

Search

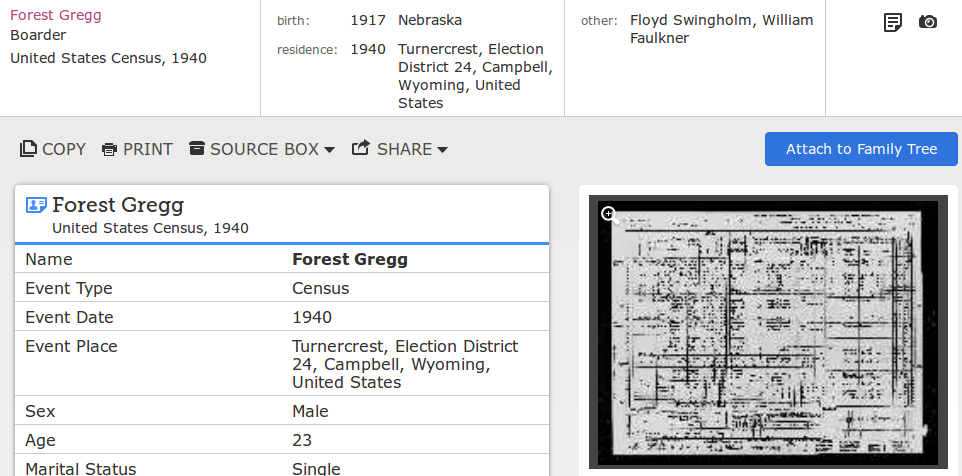

The search results show the name and other information that have been extracted from the source record. Clicking on a result shows details about the source document, all information extracted from the source document related to the focal person, and a link to an image of the source document.

Search Detail

If the user decides that a record is relevant to her person of interest, she will click the “Attach to Family Tree” button, which takes the user to a “source linker” page. Here, she sees a two-column view where she can align references that appear in a record to persons with existing profile pages.

Source Linker

For each reference, the user can decide to link it to a person or not. If a piece of information is in the record but not in the profile, it can be added. Information added here will show up on the profile page and be linked back to the source record.

Add Information from Source Record

While FamilySearch.org has many other sophisticated features, the last we’ll touch on is the view they make available for the connections between persons. In addition to the person-focused information available on a profile page—parents, siblings, children, and spouse—the site also provides a network view of these relations as family tree.

Family Tree

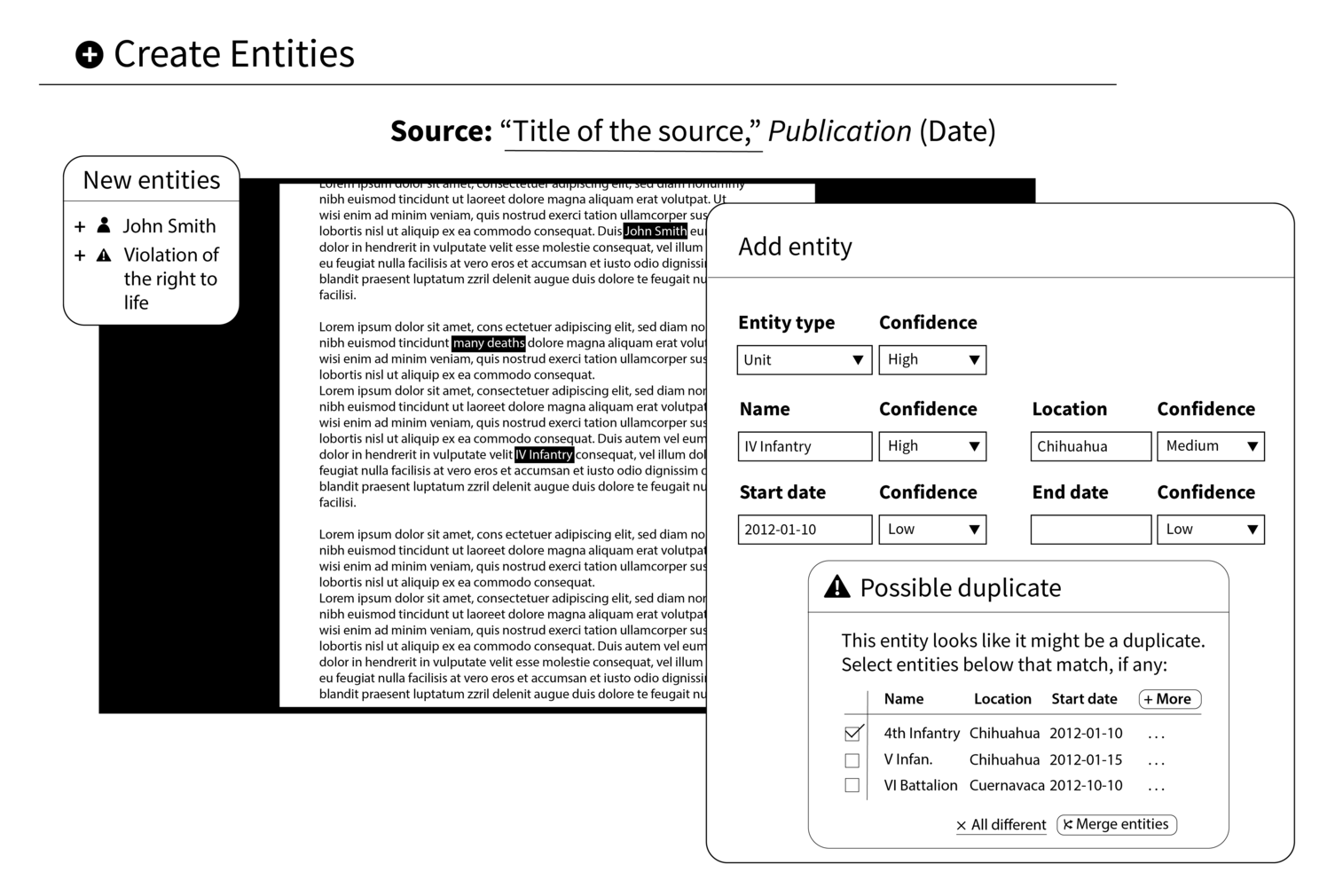

Security Force Monitor Implementation

The staff of the Security Force Monitor use news articles to build accurate information about the security forces active within a region of interest, their organizational structure, and the careers of officers within that structure.

The knowledge management system that DataMade is building with Security Force Monitor has many of the same types of elements as FamilySearch.org. The similarities and differences demonstrate the requirements for this type of system.

Like FamilySearch.org, current information about an entity will be available on a profile view. However, the Security Force Monitor needs to manage information about two types of entities: officers and organizational units. For an officer, we will track the name, appearances at particular places and times, membership in organizational units and the role associated with that membership, and the directly superordinate and subordinate officers at particular times.

For organizational units, we will record the name, observations of the unit or members of the units at particular places and times, direct superunit and subunits of the units, and the history of commanding officers of the unit.

Profile View

Unlike Family Search, the Security Force Monitor workflow is not sharply divided between source document acquisition and indexing on one hand versus claim management on the other.

A key task for staff is to extract information about relevant people and organizations from a news item. From the user’s perspective, she is directly connecting the information in the news article to an existing profile page, but the system will actually record this information as two distinct sets of claims. First, this source document mentions an entity with this name, i.e. ‘XI Battalion’. Second, this name references the entity known to this system as ‘X12135117’. Later, if we decide that this name actually refers to some other batallion, we can re-use the first half of the work done by the staff.

The user interface for this extraction will be provided mainly through the annotation of source documents. The user will select text from a news item that refers to an entity of interest, which will prompt the user to record a claim. The universe of possible types of claims is constrained by the system but can include claims like “A unit called ‘XI Batallion’ operates in the ‘Southern Province’ as of the time of this news article” or “The ‘XI Batallion’ is commanded by ‘John Doe’ as of the time of this news article”. Representations of these claims will appear on profile pages and be linked back to the source document.

Source Extraction

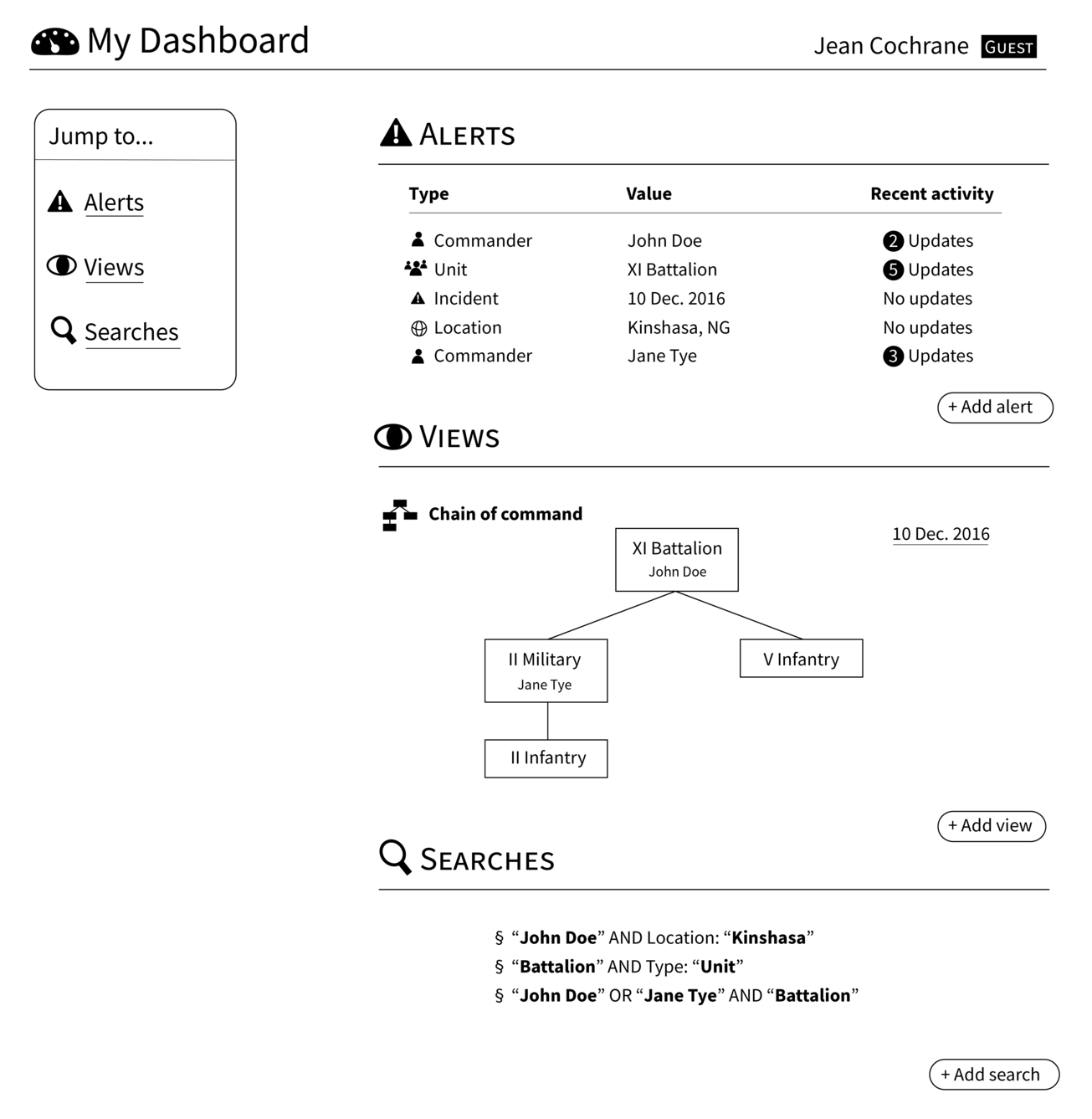

The Security Force Monitor staff will often be focused on the same area and security forces. Individual users need means to track how the changes other users are making directly or indirectly affect the entities they are responsible for. Users will be able to “watch” entities and be notified about changes that impinge on those entities as well as their own recent actions.

Watching Entities

Uncertainty in Claims

Since the work of Lotfi Zadeh, the worlds of logic and computer science have reckoned with uncertainty and partial truth using computation-friendly tools. Incorporating some measure of uncertainty into any claim (and enabling the adjustment of this level of uncertainty as new information is added) is an important part of claims management as well as detecting and reconciling conflicting claims.

Recording (and modifying) the journalist’s uncertainty about a claim only records half of the uncertainty that is possible in the knowledge system. In addition to the uncertainty in knowledge, which can be modeled, there is uncertainty in the world itself.

As a few examples, the officer who has formal authority over a security force unit may not be the person who has effective leadership. Between units, formally subordinate units may act with more autonomy than officially granted. The scope of authority between political commissars and commanding officers often overlap and are contested. Between security units, particularly those in forces that are blends of separate chains of commands, as in multinational commands, the formal chain of command can change rapidly and sometimes not in a unitary manner.

These occasions, where authority, leadership, and command are ambiguous or contested, make certain types of abuses more likely, and indeed ambiguity is often created by leadership to protect themselves from a policy of violence and oppression. Fuzzy logics offer an opportunity for not only recording but detecting this type of uncertainty, in addition to the uncertainties of the research process.

Differences in Implementation

Different knowledge domains have different research needs. When implementing a machine-assisted dossier, trade-offs will have to be made between the flexibility afforded to individual researchers and the usability of the system for a wider collective. Specific implementations of the system we propose will vary in the degree to which they permit the following features:

-

Conflict resolution. It may be beneficial to some systems to allow conflicting claims about entities or attributes to coexist, and to expose these conflicts to users. Other systems will want to enforce a unitary vision of the world.

-

Custom attachments. Researchers may wish to collect unstructured data in the system, in order to keep track of information they might need at a later date, or to pursue promising lines of inquiry that have not yet proven to be valuable to the collective.

-

Interface between document collection and claim management. When conflicting claims get resolved, it is likely that logic will want to propagate down toward decisions made in the lower levels of document collection. Some systems will want to adjust these lower levels automatically; others will want to expose inconsistencies to researchers through the system interface, to allow them to adjudicate the claims. Still others may wish to permit logical inconsistencies.

Conclusion

We have discussed what we see as necessary for a knowledge system that helps journalists and other types of researchers do their research and, as a byproduct, produce reusable knowledge for themselves and their colleagues. In particular, we have discussed the requirements for managing claims about the world, and we have discussed possible implementations to satisfy those requirements.

While it is useful to describe clearly what those requirements are, there is still significant opportunity left to make it easier to build these types of systems in the future. As we mentioned, the document management and indexing systems are fairly mature and modular. We believe that it will be possible to see similar development in the work of claim management.

Acknowledgements

This paper benefited enormously from conversations with our patient and generous colleagues. Many thanks to Bob Lannon, Kathryn Lindeman, and Michael Castelle for their comments. We also owe a debt of gratitude to the team at the Security Force Monitor, who have given us the opportunity to put many of these ideas to the test in a practical context. Without them, this paper would not exist.

Get in Touch

Do you have thoughts about machine assisted dossiers? Interested in hiring DataMade to build one? Send us an email, or leave your thoughts on our GitHub page for the paper.

Jean Cochrane

Jean Cochrane

Tim McGovern

Tim McGovern